On the Edge: The Gulf of Mexico

- Sophia Cain

- May 7, 2021

- 7 min read

Cartography typically presents a world that can be understood as a network of manmade places that overlay and intervene in the natural world, compartmentalized by hierarchies of borders. These boundaries, whether they are defined by ink or by water, are an important part of how we understand the world not only politically but also historically and culturally. Although they tend to morph over time, normally due to political changes, they are a relatively rigid element of structure that helps us define the extents of authority, of rights, and of what's considered "home."

Consider how lines of this kind take precedence over other kinds of boundaries on a map. Despite being technically manmade and potentially changeable, they cross over geographical realities as though to actually split mountains, widen rivers, and cut the shore like a cord. They are not divinely ordained or inherent to the world; instead their importance is based solely on their importance to us. Agreed-upon boundaries are the ones we defend, and where there is disagreement conflict arises. But there's another kind of boundary that nobody attempts to negotiate with: namely, coastlines.

Outlines of the World

The edges of water bodies may be defined abruptly by sheer cliffs, softly by sandy beaches under shifting tides, or they may even be blurry, in marshy places that are something between land and water. These lines, which literally shape continents, change by imperceptible measures each day under the influence of moving water, and are nevertheless world boundaries in their own right. People might fight about who owns them, but we don't get to redraw them to any significant extent. The shores are a parameter within which all the nations are gathered together.

If you think about it, a coastline is a very long line, crossing borders without any documentation as it traces the edges of the world. Wherever humans choose to draw our defining boundaries, we do it within the scope of the boundaries set for us by the edges of the seas. Today, let's simply switch the roles of importance held by manmade and natural boundaries in a map, focusing not on a region bounded by the sea but on a sea bounded by regions. For this we'll look at a sea situated among many lands: The Gulf of Mexico. Click the map below to enlarge.

This map focuses on land use along the Gulf Coast in order to consider the coastline along the Gulf of Mexico as a continuous line, and to visualize the spatial relationship between the built and natural environments along that line. Suspending the usual cartographic focus on human civilization, we have forgone the border lines between nations and between the states within them. The only part of these borders we're looking at are where they terminate, indicated by the long slash marks where they touch the Gulf Coast. We are looking at the land the way we often look at bodies of water that have names but flow together, the way the Gulf of Mexico does with the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea.

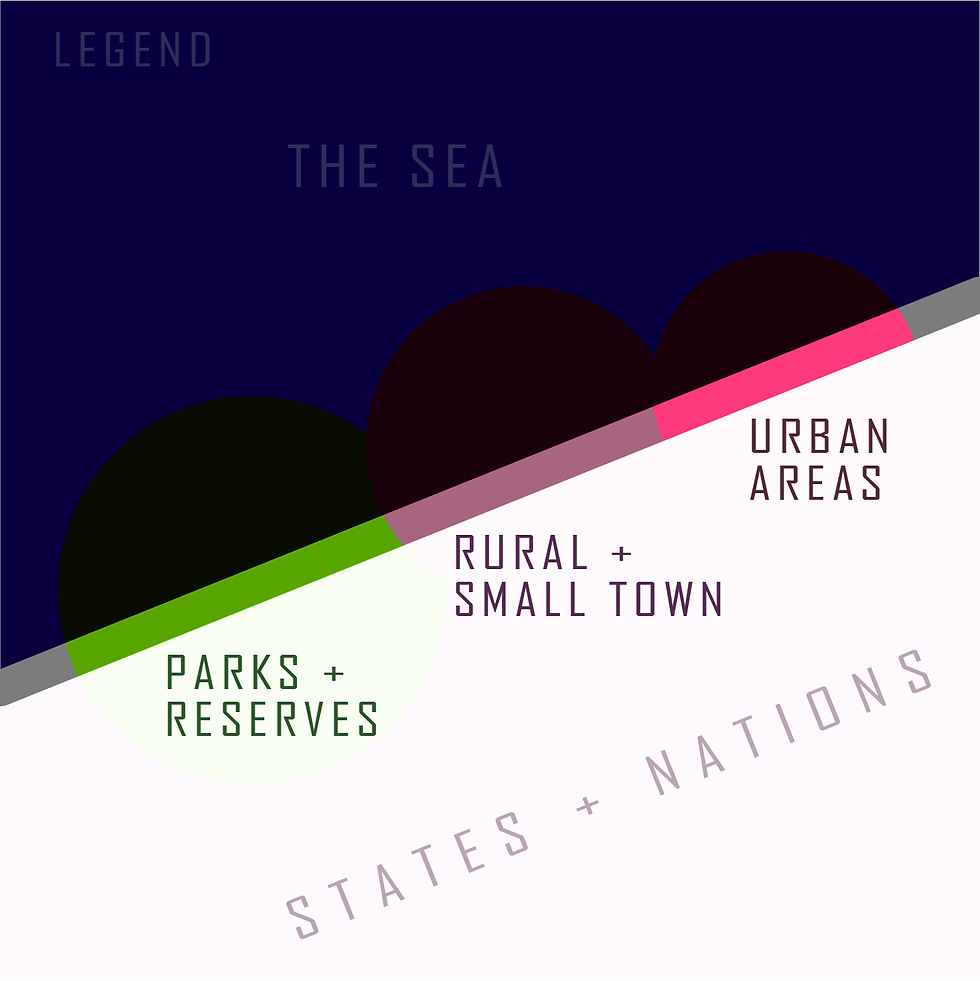

Legend

Again, agreed-upon political borders serve important purposes, but by reducing them to the points where they meet the sea and appear to divide the coastline, we can visualize how undivided the coastline actually is, and understand a politically varied group of regions in terms of their shared geographic qualities.

Consider the legend on the right. Colored bubbles are strung along a thick line representing the Gulf Coast, coloring in segments of the coastline.

The green areas are primarily natural, undeveloped areas including parks and reserves, agricultural and sparsely populated areas. In purple are the places occupied by small towns and the outskirts of major cities, where human presence is considerable but not dense. The bright pink bubbles indicate where major cities meet the Gulf of Mexico, the more populous and totally urbanized areas.

Any portion of the line that is left grey is not directly touching the Gulf, and isn't part of the Gulf Coast. The names of political regions accompany their respective portions of the coastline, marked off with thin blue slashes.

By following along the edge of the Gulf of Mexico you can see the often complicated shape of the shoreline, sometimes breaking down into groups of small islands. Let's zoom in to take a tour of the coastline's journey. Use the slideshow below to follow along.

North

We'll start in Florida for no better reason than because that's where I am right now. The Keys are flung out toward the Gulf like a broken string of pearls, falling away from the vast marshland along the Everglades. Large and small towns alike line Florida's 'sunset' side, with large portions of the coast also being dedicated to wildlife management areas and state parks. Alabama gets just a sliver of the coastline, a highly urbanized area whose most significant feature is Mobile Bay. Similarly, Mississippi has a small portion of the coast with room enough for the city of Biloxi and its outskirts.

Louisiana's share of the Gulf Coast is largely made up of low-lying marshy and island areas that constitute the drumroll finish of the legendary Mississippi River's epic journey as it finally concludes at the Gulf. New Orleans is set along an inland reach of the Gulf, and like the marshy regions of Florida much of the coast remains unbuilt and natural. There are some smaller towns on the way to Texas, where the coastline dances about and creates many little inlets and bays. Two major urban areas occur along the Texan Gulf Coast, the first being Houston and Galveston taken together and the second being Corpus Christi. Although there are many smaller towns along the way, this long portion of the coast has a lot of room designated for natural preserves and beaches, and the mouths of streams.

Then suddenly, one special river comes along and changes everything. The Rio Grande, whose name means the "large" or "great river," has come hundreds of miles to get to the Gulf of Mexico. At the end it's only a little more than 500 feet wide, but this adventurous line is bold enough not only to designate the border of the largest continental state in America, but also to signify the beginning of another country altogether. Near the city of Matamoros the Gulf Coast now meets the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, whose coast is mostly small towns dotted along beaches and lagoons until the city of Tampico right at the border of the state of Veracruz. The long coast of Veracruz meets Tuxpan de Rodriguez Cano, Heroica Veracruz, and then Coatzacoalcos, and many smaller towns dotted between, with significant portions sparsely populated and beachy.

South

Reaching through Veracruz and passing into the state of Tabasco, the Gulf Coast now fully transforms into a north coast, directly across from the southern coast of Louisiana and East Texas. Tabasco's share of the coastline sees long stretches of lagoons and reserves with a couple small towns along the way. Next, Campeche's coast is similar but with the special features of an especially large lagoon headed by Ciudad del Carmen, and later the coastal capital of Campeche.

The Gulf Coast then takes a sudden northward turn into the Yucatan peninsula, comparable to the Floridian peninsula not far away. It cuts the Gulf off from the rest of the Caribbean area. A large portion of the Yucatan coast is made up of natural reserves in addition to the capital city Merida and its outskirts. The last stretch of land to touch the Gulf of Mexico before it gives way to the Caribbean Sea is the northern tip of the state of Quintana Roo, with the city of Cancun.

Although this is the extend of the continuous coastline surrounding the Gulf of Mexico, it's important to note that Cuba has one of its own. Its own long, insular coast is situated in few of the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean. The northeast face of Cuba is largely small towns and keys until the capital city of Havana, just 100 miles from the Florida Keys where we began.

A Place Big Enough to Share

It's fascinating to consider that hypothetically a person could walk continuously from one end of the colorful chain to the other with the Gulf always on their side, as we've just done virtually. Private property, geological obstacles, weather, political boundaries, and maybe wild animals would be the main setbacks to doing it in real life. But again, it's pretty impressive that none of those things get in the shoreline's way. And then to remember that this line keeps going, around Florida, north all the way to Maine, to Canada! And south along the smaller Central American countries, all of Brazil, almost all the way to Antarctica and then it just makes a U-turn and meets the Pacific. All because a portion of the earth is at a high enough elevation to rise above the water and become a world of its own -- a world of our own.

We can best celebrate the diversity of the human experience when we consider what's continuous from my home to yours, whether it's a coastline, a coordinate line, or even just a phone line. Some commonality turns our differences from an 'otherness' to a richness. The world gets bigger when we think about how much less divided and more united many things are than they can often seem. And when the world turns out to be bigger than we thought, it might make us feel small at first, but then it makes us part of something bigger than ourselves. And it's something we each are part of, so we can think of one another as a big deal. As important as the land-bound borders between us are, we have something to gain from remembering the lines that gather us. To know I live along the same long, long coastline with so many millions of people can expand my idea of who my neighbor is, and what a big story I really get to be a part of.

Nations draw straight, imaginary, dotted lines over portions of water bodies to define who has jurisdiction, and they come to agreements on who has the right to move and operate within them. But that's only necessary because of the lines that humankind didn't determine, the edges of major water bodies that constitute the shape of all continents. We can affect it to a certain extent, and society impacts the condition of shorelines for better or for worse, but we can't pick up a nation and move it somewhere else. We are constantly drawn to it and build our largest cities by it. And just as we all seem to share this desire for the sea, we are often unified by shorelines that race past the borders between nations and states, even stretching between seas.

Comments